When addressing problem behavior in the classroom or crafting a student’s IEP, one of the most challenging tasks involves creating meaningful and measurable goals. Special education professionals, teachers, and therapists must take what they know about a student and craft tools and strategies that result in the best outcomes for the learner. One approach to. IEP Goals: S.M.A.R.T.E.R. STEPS® Guide is a 2-hour online continuing education (CE) course that provides a framework for writing legally compliant IEP goals. Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings give parents and professionals a chance to work together to design an IEP for children with learning disabilities who have been determined eligible for special education.

When addressing problem behavior in the classroom or crafting a student’s IEP, one of the most challenging tasks involves creating meaningful and measurable goals. Special education professionals, teachers, and therapists must take what they know about a student and craft tools and strategies that result in the best outcomes for the learner. One approach to make the process of developing goals more manageable (and more effective for students) is to use SMART goals.

What are SMART goals?

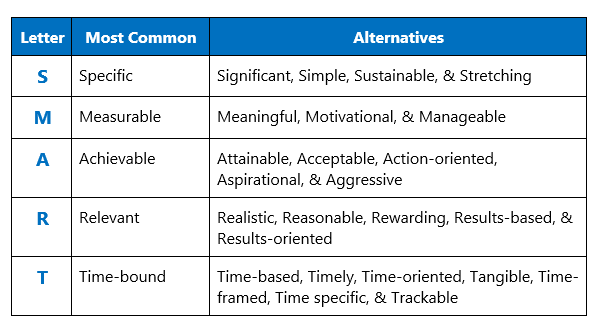

SMART describes an acronym for developing IEP goals with a specific formula for success.

The letters in SMART stand for:

S – Specific – SMART goals have a specific target behavior to increase or decrease in mind. The goal should be narrow in focus and have a clear description of the outcome.

M – Measurable – SMART goals also contain clear measurement criteria for the target behavior. If the goal includes observable measurements, different stakeholders, including parents, teachers, paraprofessionals, or non-special education professionals, should be able to read the objective and measure it the same way.

A – Attainable and Achievable – Behavior goals must be set in a way that’s attainable or achievable. Goals that are developed with unrealistic standards or goals that are not developmentally appropriate for a particular child likely won’t succeed.

R – Relevant – SMART behavior goals focus on significant issues to the child, the parents, and the classroom. Goals should be set with each child’s unique needs in mind rather than focus on obscure assessments or meeting unrealistic education standards.

T – Time-bound – Finally, SMART behavior goals have start and end times built into the goal. Understanding when progress towards meeting the goal should begin, and setting a target date for the objective to be met ensures better progress monitoring and accountability.

Examples of SMART Goals

Once you examine SMART goals for IEPs and special education classrooms, it quickly becomes apparent why they are more effective in helping students achieve outcomes. Consider two examples of a less-effective goal and how the same objective might be written differently:

Sam will make more friends on the playground this year.

During a 15 minute recess, Sam will initiate play with at least 2 different classmates and sustain play with at least 1 classmate without adult support or intervention. Sam will meet this objective on four out of five recess observations by the end of the semester.

Lila won’t get so angry when I ask her to do something.

When given a direction or instruction by her classroom teacher, Lila will complete the task in the same amount of time allotted to her peers, or will appropriately ask the teacher for help to complete the activity. Lila will meet this objective on 90% of instructions given during three one-hour classroom observations.

How to Write SMART goals for IEPs and special education behavior goals

When placed side-by-side, striking differences between SMART goals and general goals emerge. Yet writing SMART goals takes practice and experience. When first beginning to translate general goals into SMART goals, consider following these steps:

- Observe the child. It may sound obvious, but many special education professionals get tasked with writing IEP goals with little or no observation time with the child. Figure out when the behaviors occur, and plan time to do an observation before you begin to write goals.

- Review relevant documents, including the functional behavior analysis (FBA). To write SMART goals, you’ll need to know some information about the child’s history. Reviewing case documents can provide valuable information about the measurement criteria used in past goals, the relevancy of future goals, and how attainable your potential goals might be.

- Talk with key stakeholders. As part of writing SMART goals for IEPs and the classroom, it’s essential to plan to spend time interviewing critical stakeholders like parents, teachers, paraprofessionals, and other therapy specialists like speech and OT. If the problem behavior only occurs in one particular setting, the most relevant goal will tackle the response in that specific setting.

- Collect baseline data. As with any behavior goal, you’ll need to collect some baseline data during your observations. Baseline data becomes especially relevant to SMART goals since it helps establish the parameters for how you’ll measure the behavior change and where to set the attainable criteria. Without knowing how often or how long a particular behavior happens, it’s difficult to define the goal with enough specificity.

In addition to collecting baseline data on the learner, for some goals, it may be necessary to also observe and collect data on the entire classroom or other peers. Goals should be written as developmentally as realistic as possible. For example, expecting a 2-year-old to write a five-paragraph essay would not be developmentally appropriate. Whenever possible, write goals to match the expectations of classroom peers (e.g., if peers in the classroom talk out of turn 3-4 times per day, writing a goal to speak out of turn 0 times per day may not be relevant or attainable.)

- Identify a starting and ending timeline. As soon as you have an idea about baseline behavior levels, begin formulating a sense of a realistic schedule to accomplish the goal. While some goals may be bound by fixed timelines like school year or IEP deadlines, others may not need to be. Identify the starting point and then choose an ending schedule to accomplish the goal.

- Ask: What strategies might be successful in targeting this behavior? When you formulate SMART goals, also begin to formulate what strategies and interventions might be relevant. Sometimes for one response to decrease (e.g., aggression), another behavior needs to increase (e.g., using an iPad to request). At that point, it may be necessary to write a secondary or related SMART goal. Formulating the strategies needed to succeed at the same time gives a goal the highest probability of succeeding.

- Ask: What milestones will help me know this goal is met? Along with writing your goals, you’ll also want to consider what the ‘finished product’ might look like. If the child is now demonstrating an acceptable level of performance, how will you know? Does the child’s behavior match his or her classroom peers? Does the child show 25%, 50%, or 100% improvement?

Once you have an end picture, it can also be helpful when crafting a SMART goal to create milestones or markers along the way. These markers should also fit the smart parameters, meaning when you’re half-way to meeting the overall goal, you should still have a measurable and attainable milestone as a guide. Knowing what markers you’ll use to measure progress along the way can help draft a better SMART goal.

- Write the goal. Once you’ve observed, established baseline, and brainstormed about the timeline, strategies, and milestones for a goal, it’s time to write. Choose a dedicated time to write goals without any distractions. Then set finished goals aside for a few hours and come back to them. Sometimes taking a second look at a later time can lead to tweaks and changes that ultimately make SMART goals more precise and more valuable to the child.

- Have a trusted colleague review the goal. Finally, it’s always helpful when writing SMART goals to have someone else review them. If you’re unsure about whether a target is specific and measurable, a third-party less familiar with the child or a classroom can provide helpful feedback. Offer to be an “IEP goal reviewer” for a co-worker or colleague if they’ll offer the same constructive feedback for your own goals.

Finally, as you develop SMART goals, it’s important to remember that the IEP process is meant to be collaborative and consultative. No one-size-fits-all approach exists for writing goals and for working on SMART targets for children. Involve other stakeholders, gather as much information as possible, and seek out feedback whenever possible. These strategies and steps will only help you write better goals and see better outcomes for students.

Amy Sippl

S.m.a.r.t Goal Setting Dialectical Behavioral Training Objectives

Applied Behavior Analysis | Saint Cloud State UniversityBachelor of Arts (B.A.), Psychology | University of MinnesotaApril 2020

More Articles of Interest:

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

- What are the Characteristics of a Teacher Using ABA?

- How Does Research Support Applied Behavior Analysis?

- Is EFT Tapping Effective with Those with Autism?

- How Can You Prevent or Replace Attention-Seeking Behavior?